Growing up in Hong Kong, I’d always had the impression that US education styles were completely different from those that I experienced at home. It wasn’t until my first trip to the US, to study in Middlebury College, that I realized how deep those differences ran, underscoring the impact of social and political context on the role of students in education. Like most other Hong Kong students, I kept my head down in school and rarely joined extracurricular activies, and spent most of my time studying to excel in exams. This was a total contrast to the curriculum I experienced at Middlebury, where professors were very laid back and got offended if you didn’t call them by their first names, and the bulk of my grades rarely, if ever, relied on exams. In addition, I also held many leadership positions in student organizations and student government for the first time in college, which play a much smaller role in Hong Kong schools.

Hong Kong’s education system, like many others across the Asia Pacific region, is built on a rigid top-down approach, where student input is minimized, and students have all aspects of their school lives directed by teachers and faculty. Under a system of ‘boss management’, students are often discouraged from taking initiative and have no opportunities to do so, which limits student creativity and perpetuates conformation to adult ideals and to societal norm. This system often doesn’t take into account the generational shifts in ideologies and values, and in some ways also causes students to stagnate in their creative development. In my experience, this makes it difficult to implement models of Youth-Adult Partnership, and would make it difficult to emulate UP programs in a Hong Kong context.

That’s not to say that alternative educational structures don’t exist in Hong Kong— like most other metropolitan cities, Hong Kong has a large number of private and international schools, which implement European and US education models like the International Baccalaureate and the AP system. These institutions place a strong emphasis on Youth-Adult partnership, as private schools pride themselves on nurturing student initiatives. Unfortunately, these opportunities are often limited to wealthier demographics, as private schools are incredibly expensive while local schools remain free. The majority student-founded and youth empowerment organizations that exist in the city are populated by privileged students from said private and international schools. This further reinforces the notion that restrictive education in local schools may contribute to students feeling less empowered to make an impact, both within and outside of school contexts.

The political context of Hong Kong’s unique situation has also always impacted its education sphere, as restrictions on student agency in Hong Kong schools are also strongly intertwined with restrictions on post-2019 political movements. Students have played a key role in Hong Kong politics, and this is most clear when considering the successful instance of student-led political movements in 2014. Student-led group Scholarism led the Class Boycott Strikes that year, which ended up being the trigger for the city-wide 2014 protests– the precursor to the pro-democracy protests of 2019.

The direct link between student activism and the pro-democracy protests of Hong Kong led to students and youth being additionally targeted following the implementation of the National Security Law. There are currently 1,014 political prisoners in the city: “Young people have been disproportionately targeted. More than three-fourths of Hong Kong’s political prisoners are under the age of 30, more than half under 25, and more than 15 percent are minors.” Student voices have been entirely restricted and have diminished across both tertiary and secondary levels, especially as a majority of public figures of the protest movement were university students. In response, numerous universities have banned their student councils, with secondary institutions following suit.

While there have been instances of successful Youth-Adult Partnerships in Hong Kong, they are largely limited to international and private schools that follow European and US models of education, and are exclusive to wealthier students. The prevailing cultural context, which undervalues student input, and broader political landscape of Hong Kong today have perpetuated a society in which student voices are largely stifled. Students today have little to no ability to self-advocate across all year groups, including elementary, secondary and tertiary education levels. I certainly felt it in the atmosphere before leaving for college, and it made me all the more determined to take advantage of international opportunities, and the flexibility that Middlebury’s liberal arts curriculum offers me. It has been clear throughout the city’s protests that student voices are incredibly powerful— whether this will be allowed to flourish in the years to come remains to be seen.

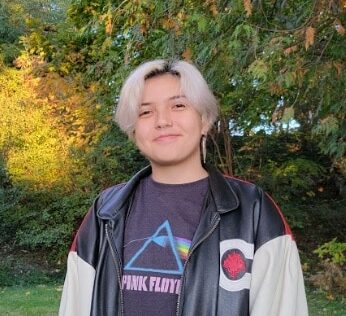

by Kaveh Abu Khaleel, UP for Learning Intern